November Case of the Month: An Unwanted Flap

This summer, Lilly was turned out on pasture with her herd mate overnight, like every other night. However, the next morning proved to be unlike any other morning when her owners were shocked to find Lilly with a large wound to her chest. Overnight Lilly had torn a large flap of skin away from the underlying tissue across her right shoulder and pectorals, as well as cut into the muscle in one spot over the shoulder. The first thing Lilly’s owners did was to call us and send photos. It was very clear that Lilly needed to be seen on emergency to try to save that damaged tissue. Dr McDonald repaired the laceration in the muscle over Lilly’s shoulder, as well as closing the skin flap back over all that exposed subcutaneous tissue and muscle. You’ll notice in the photos of the repair that she placed a sterile drain at the very bottom of the wound to allow blood and serum to drain out of the wound space and allow the tissues the best chance to re-adhere to one another.

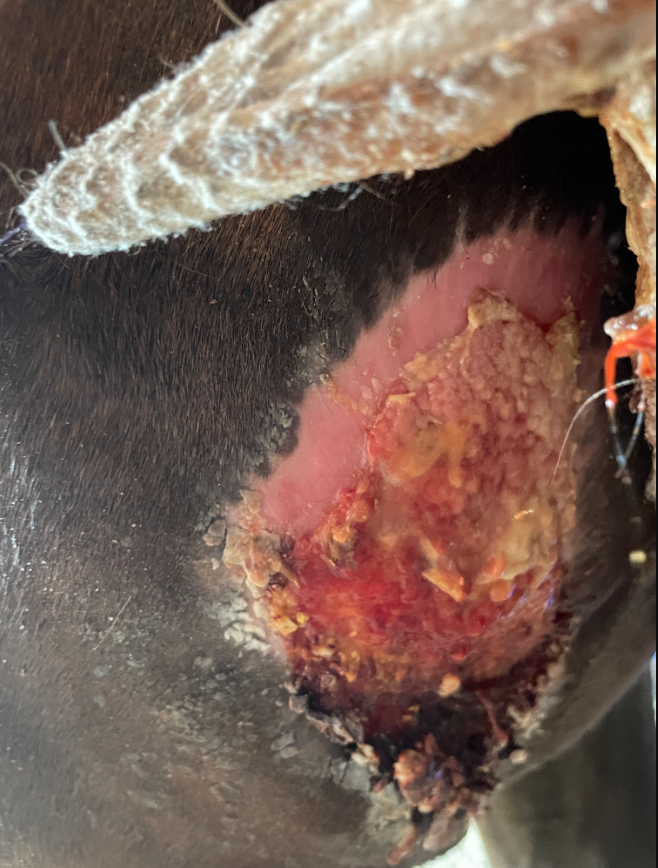

It is not uncommon for horses to suffer from large skin flap lacerations like Lilly’s, and while we will never know what caused Lilly’s wound, in many cases these lacerations result from the horse either running into a stationary object at speed or catching their chest skin on something and rearing up and back away from the source of pain. It is very typical for the skin flap created by these lacerations to have a narrow base attaching it to the unaffected skin, which can lead to complications in the healing process. With only a few remaining intact skin blood vessels, oftentimes much of the flap suffers from poor to no blood supply and will end up dying off (also known as necrosis). As you can see in looking through the photos of the progression of Lilly’s wound healing, her skin flap had started to necrose at the two pointed edges by day 5 (you can tell this because the skin is getting wrinkled and looks thick and tough), with the majority of the flap dying and pulling away from the living skin by day 11. Many people will ask with an outcome like this, why do you bother to spend the time to suture the skin back in place if you know it’s likely to die soon after? The reason is that we don’t know at the time how much of the flap will survive vs necrose, and while the skin is in place – even if it doesn’t survive – it provides a protected, healthy environment for the tissue underneath to begin to repair itself.

For Lilly’s wound, once most of the skin flap had necrosed and pulled away from the healthy skin and wound bed, Dr McDonald saw her again to trim away the dead tissue. This left a large area of exposed granulation tissue (which unfortunately Dr McDonald did not get a photo of) which still provided protection from drying out and contamination. Because the shoulder is an exceedingly difficult area to get a bandage to stay in place, Dr McDonald placed a tie-over bandage on Lilly’s shoulder. A tie-over bandage involves placing several large loops of thick suture material through the healthy skin around the edges of the wound, and then using these loops like shoelace eyelets to feed a long line of gauze or umbilical tape through in a criss-cross pattern across the wound and then cinch it down over bandage material to hold it in place. You can see Lilly’s tie-over bandage in place on day 21. Lilly’s owners diligently cleaned her wound and applied flamazine to keep the new skin and granulation tissue moist and protected and laced up her bandage to keep it all in place. After a little over a week with the tie-over bandage in place it was no longer needed and they continued to manage the wound with fly repellant around it and manuka honey over the ever-shrinking wound bed. Lilly healed up beautifully with just a small scar to remember her ordeal by, although now that she’s grown her winter coat in, you can’t see it at all, save a few white hairs.

- Lilly Day 1

- Lilly Day 1 – Partial Repair

- Lilly Day 2

- Lilly Day 5

- Lilly Day 7

- Lilly Day 11

- Lilly Day 21 with her bandage

- Lilly Day 21

- Lilly Day 30

- Lilly Day 75

- Lilly Day 95

- Lilly Day 175