July Case of the Month: An Odd Swelling

This summer our patient “Jenga” developed an odd swelling of his upper inner hindlimb with an associated lameness, but no visible wound. At that time, it seemed like Jenga had strained the muscles of his inner thigh and/or hamstrings based on the swelling and sensitivity pattern, and ultrasound evaluation of the swelling. Jenga was treated with anti-inflammatories, antibiotics to address a possible cellulitis, and stall rest with hand walking.

Over a period of one week, Jenga made some improvements, but the swelling did not completely resolve, and then, along with one of the 3 other horses on the farm, Jenga developed a fever. The second horse’s fever lasted only a short while and she made a full recovery. Jenga continued to have an intermittent fever that was controlled by Banamine, and fluctuating levels of swelling in his leg, sheath and on his belly. These symptoms lasted for approximately four and a half weeks before an abscess developed and ruptured on the left side of Jenga’s scrotum. One possible cause of a scrotal abscess is a condition known as a scirrhous cord, where the remnant of the spermatic cord develops a lingering infection following castration, even years after the fact. The correction for this condition is surgically removing the affected cord, and so we were preparing to send Jenga to a referral hospital for surgery but took a sample of the pus from the abscess to culture the infection prior to committing to surgery. Just in time before Jenga underwent surgery, the culture results came back as positive for Streptococcus equi equi, or the bacteria that causes strangles! This meant that Jenga did not in fact have a scirrhous cord, but rather he was suffering from a case of bastard strangles.

Bastard strangles is a condition where the Streptococcus equi equi bacteria disseminates through out the body rather than remaining in the upper airway, leading to abscessed lymph nodes in locations other than the throat. Once Jenga’s abscess had opened and started draining, he improved rapidly with a course of antibiotics. While Jenga was recovering, we had to put the farm under strict quarantine measures while we sorted out where the infection had originated and made sure none of the horses were actively spreading the infection. To do this, we scoped the upper airways of all four horses on the farm to visualize their guttural pouches for signs of chronic infection and collect samples of the bacterial population present. From this testing we found that Jenga’s newest herd mate, a miniature gelding named “Rocky” had a chronic, non-clinical strangles infection inside his left guttural pouch. The guttural pouches are common hiding places for lingering infections as it is difficult for the horse to clear debris from the pouches, and bacteria can colonize with minimal interference. We were able to help Rocky clear his infection by treating him with oral antibiotics, flushing his guttural pouch with sterile saline to remove the bacteria-laden pus and debris, and instilling an antibiotic gel into the infected pouch several times over the course of several weeks.

Prior to lifting the quarantine the farm was under, each horse had to have 3 nasopharyngeal wash samples test negative for the bacteria over a period of 3 weeks. This repeated testing is done because sometimes the bacteria can be shed intermittently, and we want to be sure there’s no remaining infection before allowing these horses back into the general horse population to ensure they won’t be spreading strangles to others. Jenga and Rocky’s owner was fantastic through this whole stressful ordeal, and followed the quarantine requirements diligently. Thanks to her efforts and the treatment provided by Swiftsure Equine’s veterinarians in consultation with internal medicine specialist Dr. Parsons of Parsons Equine Internal Medicine, no other horses contracted strangles from this farm, and all four horses are happy and healthy once again.

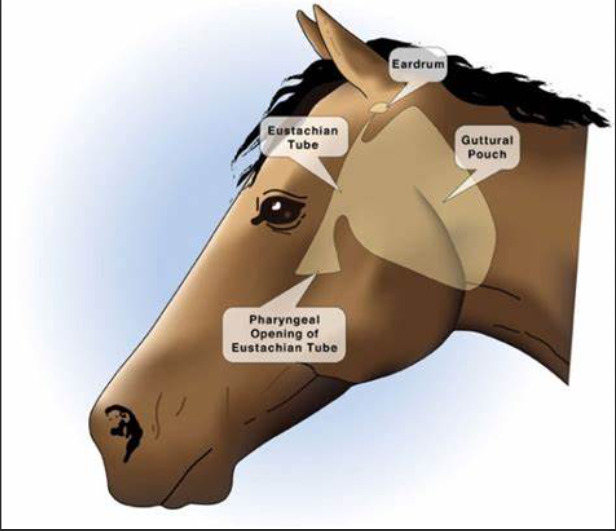

- The guttural pouch is a modification of the eustachian tube unique to horses, where the tube has a large, air-filled outpouching. Within the guttural pouch we can visualize the stylohyoid bone, and numerous blood vessels and important nerves.

- The guttural pouch is a modification of the eustachian tube unique to horses, where the tube has a large, air-filled outpouching. Within the guttural pouch we can visualize the stylohyoid bone, and numerous blood vessels and important nerves.

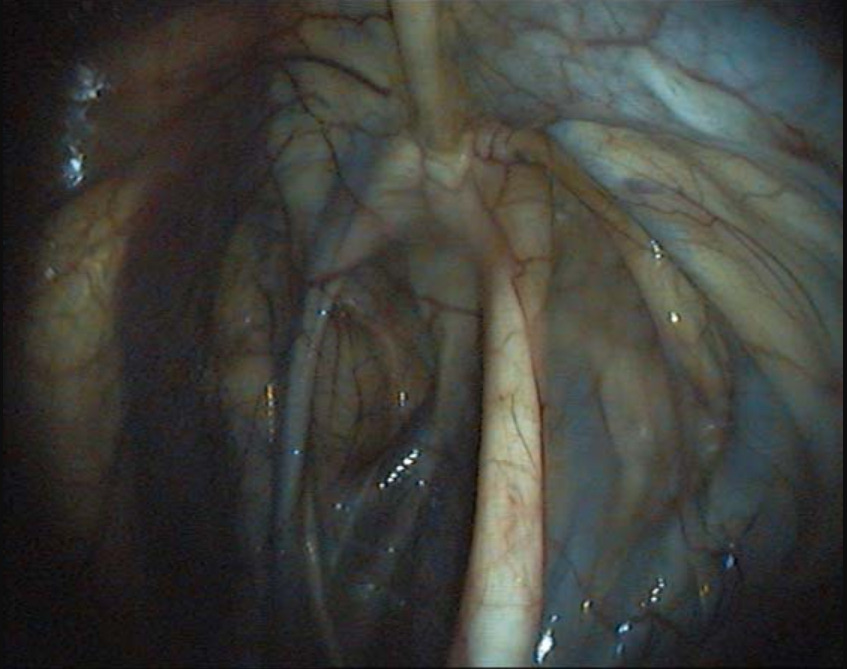

- This is an image captured from “Rocky’s” upper airway endoscopy showing large volumes of pus draining from the opening to his left guttural pouch.