February Case of the Month: Gastroscopy Explained

So, you’re concerned your horse may have gastric ulcers; maybe he’s been a bit colicky lately after eating his grain, or he’s started making angry faces when you tighten his girth, or he kicks out when you ask him to canter, or any other number of possible symptoms. The next step to confirm first if your horse does in fact have gastric ulcers, and secondly the type and severity of ulcers present, is gastroscopy. This procedure involves passing our 3.5m long endoscope into the horse’s empty stomach by way of their nostril and esophagus. An endoscope is a long, tubular camera with a bright light at the tip of the mobile end of the tube. The endoscope is connected to a processor which allows the veterinarian and you to visualize the inside of the horse’s esophagus and stomach in real time as the endoscope is passed into and out of the horse. The controls of the endoscope allow the veterinarian to steer the end of the endoscope up, down and side-to-side, to pass air and water into the stomach to clean the scope camera and clean feed debris off the stomach lining, and to freeze the camera image to allow clear photos to be taken to include in the horse’s medical record. It is important that the horse has been held off food and water for a long enough period that their stomach is empty, otherwise it can be difficult to maneuver the scope around the remaining feed, or the veterinarian may be unable to visualize a portion of the horse’s stomach.

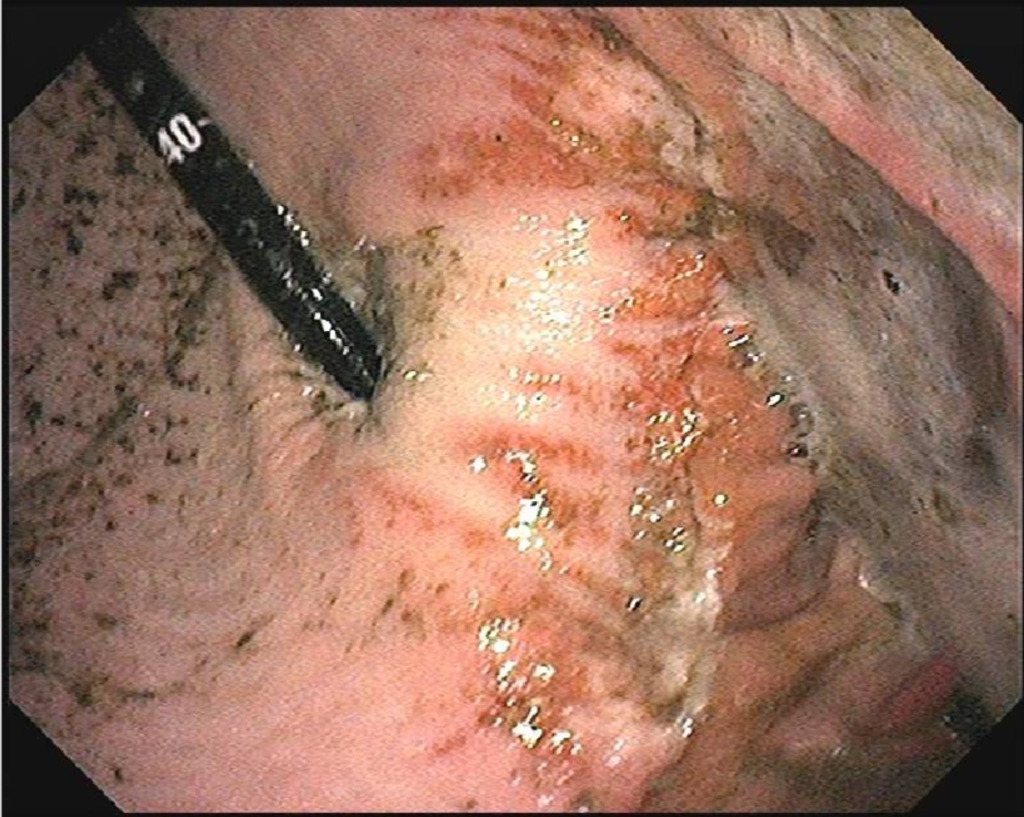

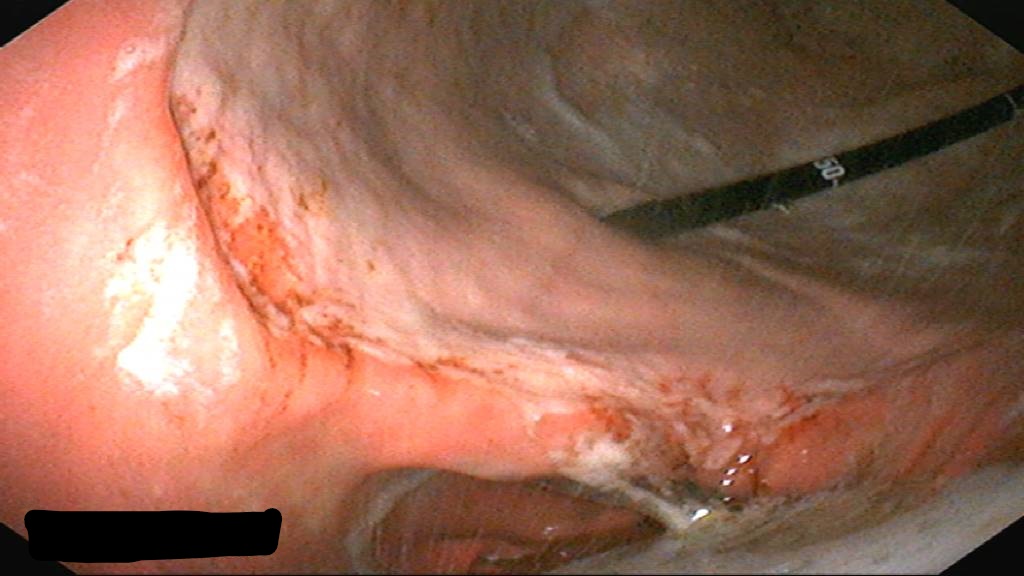

The process of a gastroscopy starts with a brief physical exam of the horse, and then the horse is sedated. Typically your veterinarian will use a level of sedation similar to that used to float your horse’s teeth for the procedure. Once the horse is sedated, the lubricated endoscope is passed up one of your horse’s nostrils into their pharynx, where the veterinarian will position the scope such that the horse can swallow the scope, allowing access to the esophagus and eventually the stomach. Once inside the stomach, the veterinarian will distend your horse’s stomach with air to allow for clear visualization of the stomach lining, and the search for inflamed or ulcerated tissue begins. The two different tissue types that line the equine stomach can each be susceptible to developing gastric ulcers, and any particular horse may have one, both, or neither variety of ulcers. The upper portion of the stomach is lined with squamous epithelium, and the lower half is glandular epithelium. The most common site for squamous ulcers is at the mid-point of the stomach where these two tissue types meet, and for glandular ulcers the most common site is at the very bottom of the stomach, called the pylorus, where the stomach connects to the small intestine. Once the veterinarian has been able to visualize all areas of the stomach, collecting photos as needed, then the endoscope is pulled back out of the horse and they recover from their sedation just like after they’ve had their teeth floated. The most effective treatment protocol for the horse can then be decided upon based on the findings from the gastroscopy.

Gastroscopy is quite a safe diagnostic procedure for the horse, the most common side effect being a mild nosebleed due to irritation from the scope in their nasal passages. Although larger nose bleeds can occur sometimes as well, they are not a significant risk to the horse’s health, they just make an unfortunate mess of the barn aisle! In very rare cases horses can show mild colic symptoms following a gastroscopy, which is thought to be secondary to the air used to distend the stomach to allow for effective visualization or may be due to the sedation. In the majority of cases though the air passed into the stomach dissipates through the gastrointestinal tract and causes no issues.

If you’re concerned your horse may have gastric ulcers, contact our office to talk to a veterinarian and determine if gastroscopy is warranted as a diagnostic step for your horse.